The Dinner Party is a monumental work of art that employs numerous media including ceramics, china-painting, and an array of needle and fiber techniques, to honor the history of women in Western civilization.

The Dinner Party is a monumental work of art that employs numerous media including ceramics, china-painting, and an array of needle and fiber techniques, to honor the history of women in Western civilization.

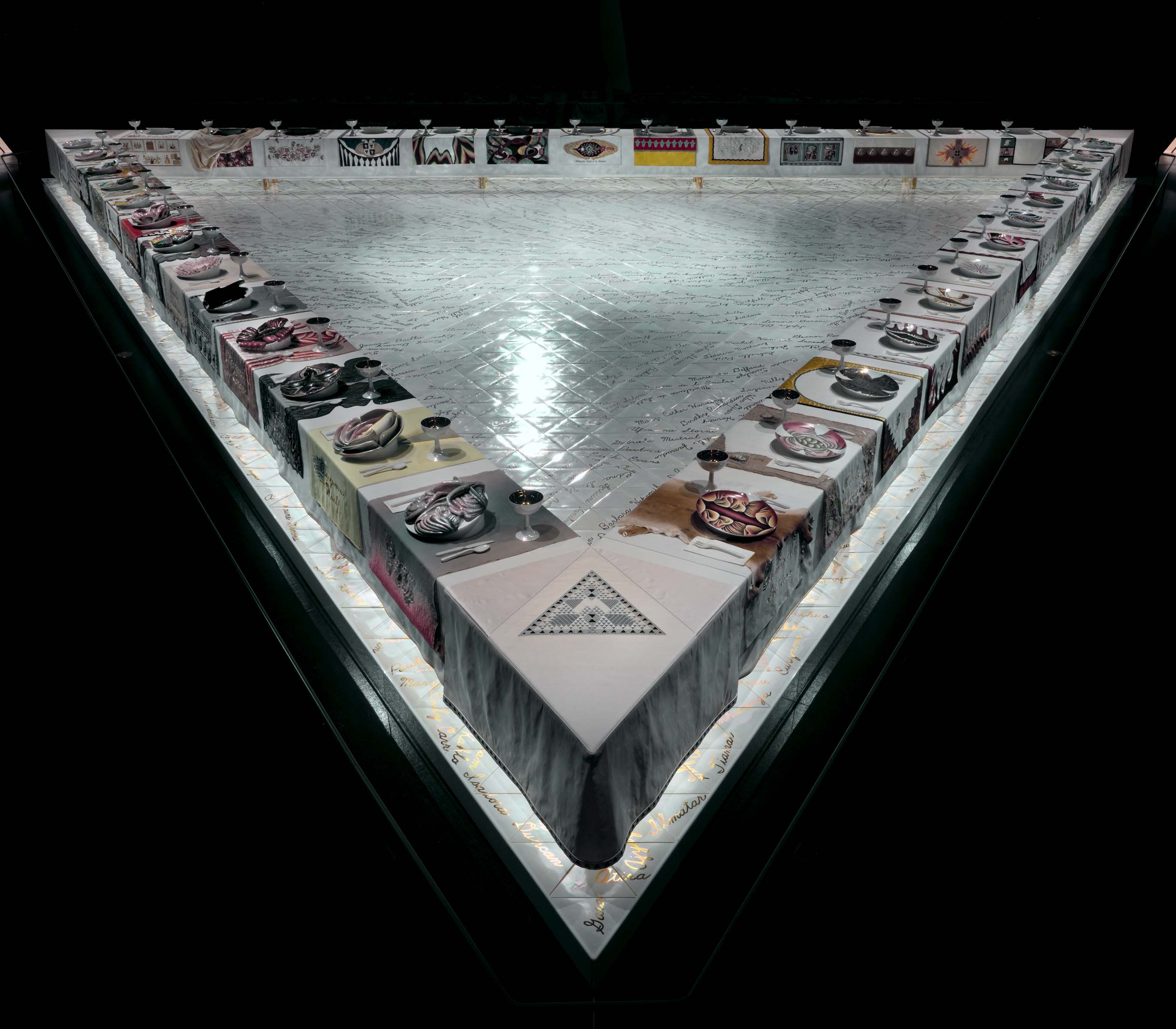

Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party elevates female achievement in Western history to a heroic scale traditionally reserved for men. The Dinner Party is a massive ceremonial banquet in art, laid on a triangular table measuring 48 feet on each side. Combining the glory of sacramental tradition with the intimate detail of a carefully orchestrated social gathering, the artist represents 39 “guests of honor” by individually symbolic, larger-than-life-size china-painted porcelain plates rising from intricate textiles draped completely over the tabletops. Each plate features an image based on the butterfly, symbolic of a vaginal central core. The runners name the 39 women and contain images drawn from each one’s story, executed in the needlework style of the time in which each woman lived.

Vivid imagery on the runner backs is visible only across the span of a gleaming porcelain floor that undulates with the gilded names of 999 women who prefigured and supported the towering figures on the table. The Dinner Party is introduced by six Aubusson tapestry banners which convey fragments from a poem by Judy Chicago, offering the dream of a more just world. The variety of details worked into the art would be overwhelming but for the powerful simplicity of the triangular form, holding a host of particulars in its equilateral embrace.

The multiplicity of lives alluded to in The Dinner Party would be impossible to take in except for one overarching fact communicated throughout the art: all these remarkable human beings were female. In the 21st century, for the Western world, the existence of women of achievement is not big news. But in 1979 (when The Dinner Party premiered), it was paradigm-shattering.

When Judy Chicago began thinking about The Dinner Party in the late 1960s, there were no women’s studies programs, no women in history courses, no seminaries teaching about the female principle in religion, and scarcely any women leading churches. There were no exhibitions, books, or courses surveying women in art. Not one woman appeared in the standard art history college textbook by H.W. Janson. There was no biography in English of Frida Kahlo and the music of Hildegarde of Bingen had not been heard for centuries.

It was more than news. It was a major challenge to academic and artistic tradition that the subject matter of women’s achievements was adequate for a monumental work of art. Developing this subject matter; expressing it traditionally on a heroic scale in media that were considered beneath the standard of fine art; working openly with scores of studio participants and acknowledging their role in the production of art, in all these ways Judy Chicago defied tradition and challenged the usual boundaries of the contemporary art world.

In 1979 the work was premiered to enormous public enthusiasm by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, whose director, Henry Hopkins, had followed its progress and supported it with grant applications in the Museum’s name for years. But the next planned stops on its exhibition tour were quickly scuttled. It was then that Through the Flower stepped in to bring The Dinner Party to the many viewers who were clamoring to see it even in the face of art world resistance and hostility which grew out of the convention-shattering nature of The Dinner Party.

Chicago’s uncommon range of abilities and her emphasis on education turned the tide. Knowing that women’s achievements—especially in the arts—had disappeared from history, Chicago planned two volumes and a film documenting The Dinner Party so that it would not be easily erased. She had already published an autobiography, Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist (1975) in which she detailed her effort to construct a historical context for her life as a woman artist. Her effort came to fruition in The Dinner Party as volunteers scoured libraries for women in history, while others gave countless hours alongside Chicago in the studio where ceramics and textiles were made. Neither Chicago nor her colleagues imagined that her book would launch The Dinner Party when the art world could not, but that’s what happened. Hundreds of thousands of visitors were moved by it; it stirred strong passions, evoked arguments among highly trained professionals, inspired parodies and imitations, even gave rise to a wave of elementary-school projects where children honored the woman of their choice by decorating a paper plate.

After its premiere, The Dinner Party went on a nine-year international tour sparked by grassroots efforts to find exhibition venues for the piece. The tour began in North America at the University of Houston at Clear Lake, Texas, and continued to venues in Boston, Brooklyn, Cleveland, Chicago, Atlanta, and across Canada. The tour continued through Europe at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, Scotland; The Warehouse, London; and Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, Germany; ending at the Royal Exhibition and Conference Center in Melbourne, Australia, in 1988. The exhibitions were hugely popular, drawing large crowds at every venue—for the European tour alone the total viewing audience was over a million people.

As The Dinner Party traveled, the culture it was part of slowly shifted. Women’s studies joined existing specialties on college campuses. Women’s rights were slowly won in the workplace, the courtroom, and the schoolyard. Some churches yielded to women’s demands for leadership roles. In the art world trends that had first emerged in California Feminist Art began to sweep the country among young artists both male and female. Materials ranging from fabric toys to paper clips became part of contemporary art making. Personal subject matter made a comeback. Installation art became a standard, and historical troves were mined to yield narrative art and post-modern commentary on history. The world, even the art world, began to catch up to the point from which Judy Chicago had begun The Dinner Party.

From the beginning Chicago had set a goal of permanently housing The Dinner Party because she recognized that without permanent housing The Dinner Party, like so much of women’s cultural production, could be lost. While the project of permanently housing The Dinner Party was stalled perpetually by the high cost of creating an ongoing institutional framework for it, the growing audience for the work found it hard to believe that housing the art was not just a matter of saying “yes.” For Chicago the situation was deeply frustrating. Over and over exhibitors profited from showing the piece. On campuses, fields of study sprang up that lent context to the factual detail embodied in the art. To students, The Dinner Party was part of art history. But for a long time permanent housing was elusive despite many efforts around the country.

Then The Dinner Party’s future was secured by Dr. Elizabeth A. Sackler. Younger than Chicago, Sackler’s experience of art from many cultures was almost unique. Her father, Arthur M. Sackler acquired countless artifacts from world cultures, donating them to museums along with buildings to house them. Sackler, who earned her Ph.D. in social history, had worked with museums on exhibitions and funded the repatriation of Native American artifacts. She also collected works by Judy Chicago and got to know her. Over time Sackler came to a decision; she would acquire the work and gift it to the Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY, where she is a trustee.

The trustees gave Sackler a standing ovation for her role in preserving the controversial Dinner Party and in 2012, Dr. Sackler was celebrated by the museum for her vision in establishing the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. The Dinner Party, accounts for a large percentage of the museum’s attendance.

Learn more about the Dinner Party components here.