The Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light is the vision of the world-renowned artist Judy Chicago who in collaboration with her husband, photographer Donald Woodman and a selected number of skilled artisans, spent eight years on a project structured as a journey into the darkness of the Holocaust and out into the light of hope.

Chicago and Woodman examined the Holocaust in a contemporary context, asking how this tragic event might serve as a prism through which to explore issues of victimization, oppression, injustice and human cruelty—issues that are sadly very much with us today.

In the Holocaust Project, Chicago and Woodman created a traveling art exhibition that engages viewers to think about their relationships with other people and to our planet as a whole. It casts the Holocaust as a reference point for an exploration of profound issues that relate to the human condition; past, present, and future. The Holocaust is approached as an event that happened at the core of our civilization, the heart of our culture, and in the midst of societies resembling our own. It is a pivotal event for contemporary society.

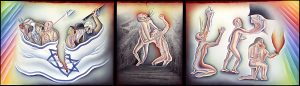

The exhibit takes visitors on a journey into one of the darkest periods of modern history through a series of artworks which includes a tapestry, two stained glass windows, and in the main part of the exhibit 13 large-scale tableaus combining painting and photography in an unprecedented manner. The art transforms the experience of the Holocaust into images that raise a series of questions about what the Holocaust means in a contemporary context.

Judy Chicago and Donald Woodman traversed the history of the Holocaust through years of extensive research, travel, and intellectual inquiry. Their journey through the literature, geography, and testimonies of the Holocaust brought them face to face with a level of reality beyond anything they had ever experienced before. Millions of people murdered, millions more enslaved, millions made to suffer. In their journey, they experienced the pain of realizing that the same world which once turned its back on the implementation of the Final Solution continues to witness human conditions similar to those which existed then. The research brought them to a new consciousness about the world and they began to understand the events of the Holocaust as part of a larger global framework. The Holocaust became a prism through which the artists formed a view of history which emphasizes the experiences of the victims rather than those of the perpetrators.

Learning about the Holocaust made the artists realize that history written by those in power can obstruct a full comprehension of the implications and impact of an event. Alexander Donat, a Holocaust survivor, recorded the words of the eminent Jewish historian Dr. Ignacy Schipper who understood the consequences of such a history when he stated:

“What we know about murdered peoples is only what their murderers vaingloriously cared to say about them. Should our murderers be victorious, should they write the history of this war, our destruction will be presented as one of the most beautiful pages of world history and future generations will pay tribute to them as dauntless crusaders. Their every word will be taken for Gospel. Or they may wipe out our memory altogether, as if we had never existed….”

Though Dr. Schipper’s trepidation never came true, Holocaust survivors—the victims—emerged to tell the world about their own experience; the Holocaust awakened the artists to transform that recorded history into unforgettable images. Elsewhere, the history often taught in our schools is largely the history of those in power. The history that has been largely ignored is the history of those who have suffered the effects in progress, of those who have been powerless to change the course of events, of those who have been the victims of power. In Dachau, we saw the way history was being erased and the Jewish experience denied. “The denial of a people’s history is part of a denial of their identity and is directly connected to their continued oppression,” writes Judy Chicago. The artists committed themselves to the premise that their work would present aspects of the human experience that have been forgotten in history, omitted from history, or distorted by history. Ultimately, their mission maturated to a presentation and study of those who have been unable to speak for themselves. Like Elie Wiesel, the artists believe that we must serve as carriers of empathy, as watch-people for the vulnerable.

Identification with vulnerability has led both artists to an increased compassion and a sense of connectedness to other living creatures on earth. The question they pose is: how do we create a world where we can be both vulnerable and safe? To help them find the answer, they examined the Jewish experience at its most vulnerable moment in time – the Holocaust. For them, the Jewish experience at its darkest moment holds the potential for broadening our understanding of the planet and its future. Along with Elie Wiesel, they arrived at a deeper understanding of the connection between what happened to the Jews and what can happen to our planet as a whole. When Elie Wiesel once contemplated the potential horror of nuclear omnicide, he stated:

Once upon a time it happened to my people, and now it happens to all people. And suddenly I said to myself, maybe the whole world, strangely, has turned Jewish. Everybody lives now facing the unknown. We are all, in a way, helpless.

The Jewish experience during the Holocaust can become a guide to learning about the vulnerability of all human beings, the endangerment of species and the fragility of our planet.

Inviting the viewers to consider the consequences of the Holocaust, however, is not enough. The artists understand the difficult challenge of presenting this awesome event to a potentially reluctant audience. They echo the words of Dr. Ignacy Schipper, who not only grasped the potential for oblivion in history but also the implications of relating the Holocaust to later generations:

But if we write the history of this period of blood and tears – and I firmly believe we will – who will believe us? Nobody will want to believe us because our disaster is the disaster of the entire civilized world… We’ll have the thankless job of proving to a reluctant world that we are Abel, the murdered brother….

Both Schipper and the artists fully understand that the disaster that befell the Jews during the Holocaust is, in reality, the disaster of modern civilization. The issue is one of the civilized world acknowledging its own role in the execution of the Holocaust and not fleeing from it as Cain did during the murder of Abel. The difficulty is in convincing people of the reality and immediacy of the Holocaust. How else can we confront the event and draw meaning from it than to contextualize it within a global framework that places the event at the heart of our civilization’s development? Recognizing the Holocaust to be a disaster of contemporary civilization is a first step in the process of questioning some deeply-held notions we have been taught about our heritage and future.

Helen Fein, a scholar of the Holocaust, posed the same question when she wrote: “How are we to confront the Holocaust? It was not only a secular event in history but an event challenging earlier notions of history as well, leading to the repudiation of the idea of human progress.”

The artists believe that we must look deeper into our civilization’s development in light of the Holocaust and re-examine our assumptions. Through their exhibition, Judy Chicago and Donald Woodman wanted to create opportunities for people to develop a consciousness about commonly-held assumptions in order to lead them into a new consciousness about the conditions from which the Holocaust occurred. Only by coming to terms with these conditions may we yet be able to prevent another event like the Holocaust from repeating.

The artists want people to consider our potential for destruction as a human species. They want people to reflect upon what we have done, what we are currently doing, and what we potentially face if we continue along the same path that led to the Holocaust. Ultimately what is at stake for humanity is the prevention of omnicide, or the total destruction of ourselves as a species. They ask: “What is our destiny in a world which once witnessed death camps and still contains the conditions which allowed the Holocaust to occur?”

Ultimately, the exhibit asks viewers to look at what we as human beings have done to each other and prompts us to consider an important question dealing with our future survival. Now that we have learned about the Holocaust, now that we better understand the conditions which allowed it to occur, is this how we as human species, want to continue to behave? The exhibit offers no answer to the question. Rather, it helps viewers reflect upon vital issues, topics, and themes that emanate from the Holocaust and which can guide us to a higher level of behavior. In the final analysis, the artists deeply hope that their works of art can contribute to a transformation of peoples through an emphasis on values that call for a more responsible, responsive, and a responding world.

The exhibit concludes with an image and a message of hope. Using the Jewish ideal of Sabbath the artists project a vision of a world joined in peace whereby peoples, nations, and cultures are all seated in joint fellowship. The shattered shards of the vessels have been reassembled as the Jewish Kabbalistic concept of “tikkun olam,” which means the healing of the world. The image guides us to move from the darkness of the Holocaust to the light of day.